I’ve been playing around with MongoDB for a while now. The more I work with it, the more I believe in the power and in fact the necessity of polyglot persistence. Just like unit testing tools, knowledge of different persistent stores is also a power tool which every developer should have.

The following blog post is to share some experiences and information about MongoDB and it’s capabilities.

Transactions

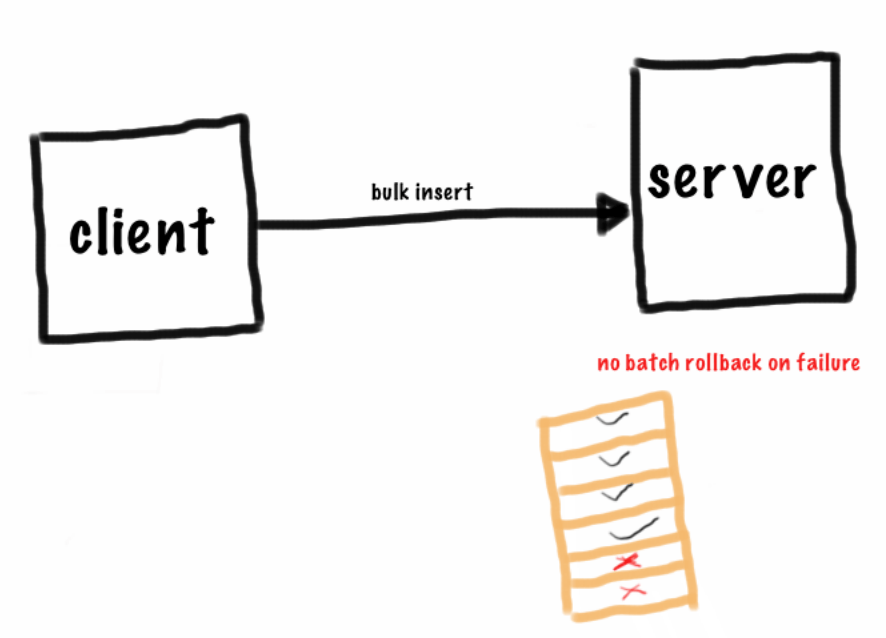

In MongoDB, the transaction boundary is at document level. Bulk / batch insert operations can be used as it leads to less bandwidth usage. But there is no outer transaction for the set of documents. If operation fails while executing batch, no rollback possible for the entire batch. It might sound a bit weird especially for someone with relational database background, but again it is not your traditional transactional relational database. Similar to SQL databases, MongoDB also supports ContinueOnError flag.

Locking mechanism

MongoDB has this controversial notion of locking. Coming from the RDBMS world, it “sounds” so wrong. I was also a bit skeptic with the whole idea of global lock (which is changed to DB level locking in 2.2). But test/ experiment before you jump to any conclusions. My experience is for most of the applications, the locking behavior is not so critical as it sounds.

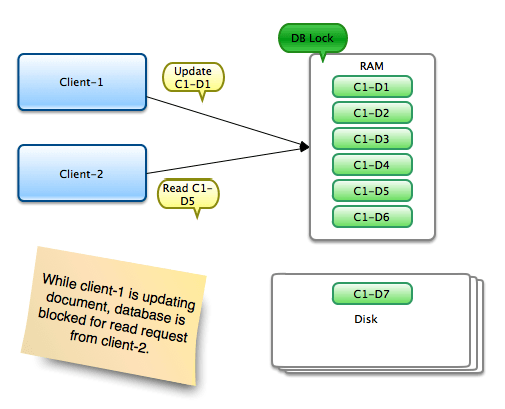

To clear some misconceptions, let’s try to understand how locking works in MongoDB. In the following scenario, client-1 is requesting an update operation on document 1 of collection 1 for instance; while client-2 s trying to read document-5. The operations are done on the same database. Note that both the documents are available in RAM. Now in this situation, while client-1 is updating a document, a lock is acquired on the database. Client-2’s read operation is blocked for a while. Once write operation finishes, client-2 gets it’s chance to finish the read operation. Since the write operation here is updating the system RAM which is a really fast operation; the blocking time for client-2 is insignificant (typically few nanoseconds).

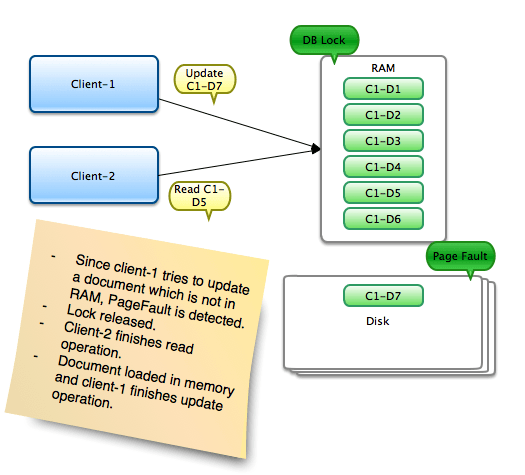

Now let’s consider another scenario where the document that the clients want to read/update (aka working set) is not available in RAM. In this situation, client-1 wants to update document-7 which is not in RAM and has to be fetched from the disk. This situation is known as Page Fault. Since fetching the document from disk can take some time; as OS has to find out if there is enough space in RAM. If there is enough space, data is read into memory. But if there is no enough space; then it has to find out the least used page; write to disk; and then read the new data into memory. While this is happening, instead of blocking other operations; the lock is released. In our case, client-2 finishes its read operation. Once the document-7 is available in memory, lock is acquired again and update is completed. In general, it is recommended to keep the working set in RAM as read/writes can really be fast when data is available in RAM.

Support for binary data storage (GridFS)

GridF is one of great features of MongoDB. It is a storage mechanism for storing large objects in MongoDB. GridFS stores the binary data into two collections namely “files” and “chunks”. The “files” collection holds the meta information about the content. It is also possible to store the user specific metadata about the content; which can come quite handy for lookups. The actual content is stored in “chunks” collection. If the content is bigger than 256MB, it is divided over multiple chunks.

There are multiple benefits of using GridFS. The traditional approach for storing content is File Store. This option works well if you want to store less data and do not bother about high availability. The performance is good as there are no levels of abstractions. But if your application demands high available and scalable store, this is not the way to go. Another approach that is used sometimes is “BLOB” storage. IMHO, this is utterly ugly. For one of the customers, I did some performance tests to compare RDBMS BLOB vs GridFS. After storing 10000 documents of 100kB each, it was disheartening to see the degradation in performance of relational datastore. On the other hand, MongoDB gave consistent performance up to 1million documents. (Note: I didn’t continue my tests beyond 1million documents; as my use case requirements were already satisfied with MongoDB.)

The point here is, relational databases are not meant to be used for large object storage. As the name suggests, they are a perfect candidate for maintaining relational structures with high transactional integrity.

Conclusion

In general, I don’t believe that one specific database is good or bad. It is rather important to select the right tool for the use case. There is no one tool to rule them all. Do not try to abuse the tools; they would have their payback time eventually.

One of the use cases for which MongoDB is a good fit is “large object storage”. Before making any decisions for your application, evaluate the possibilities. Considering the commercial and community support, available documentation and ease of use; MongoDB is definitely one of the options to be considered for polyglot persistence.

Learning Resources

- Quick introduction to NoSQL databases and their capabilities – http://pragprog.com/book/rwdata/seven-databases-in-seven-weeks

- Reference Documentation MongoDB – http://docs.mongodb.org/master/single/